Confirmed Participants

Sanjay Subrahmanyam (University of California, Los Angeles), Keynote Speaker

Yael Rice (Amherst College), Organizer

Sebouh David Aslanian (University of California, Los Angeles), Presenter

Lisa Brooks (Amherst College), Presenter

Cynthia Brokaw (Brown University), Presenter

Mitch Fraas (University of Pennsylvania), Chair

Byron Hamann (The Ohio State University), Presenter

Hansun Hsiung (Harvard University), Presenter

Aaron Hyman (University of California, Berkeley), Presenter

Ayesha A. Irani (University of Massachusetts, Boston), Presenter

Dipti Khera (New York University), Presenter

András Kiséry (City College of New York, CUNY), Chair

Dana Leibsohn (Smith College), Presenter

Brian Ogilvie (University of Massachusetts, Amherst), Chair

Indira V. Peterson (Mount Holyoke College), Presenter

Stephanie Porras (Tulane University), Presenter

Leyla Rouhi (Williams College), Chair

Nir Shafir (University of California, Los Angeles), Presenter

Abstracts

September 18

KEYNOTE LECTURE

“No want of Persian bookes of all sorts”: The Market for Books and Images in Mughal Surat (ca. 1700-1760)

Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Distinguished Professor & Irving and Jean Stone Endowed Chair in Social Sciences, UCLA

Readers of the memoirs of the eighteenth-century French savant Anquetil-Duperron would know that he spent a fair amount of time in 1759-60 at Surat, the great port of the Mughals, linking their domains to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. This was because Anquetil was on the lookout for texts, manuscripts, coins and inscriptions, all of which formed a part of his antiquarian interests. But in reality, he was hardly an exception. Since at least the early seventeenth century, Surat had been a centre from which collectors attempt to gather books and images. In February 1634, Charles I had written to the Court of Directors of the East India Company asking for a supply of Arabic and Persian manuscripts; the Company’s factors in Iran responded in late November of the same year: “Our Soveraignes requiries of your worships to furnish him with some varyties of Persian and Arabian manuscripts we shall have regard to”. But it was the head of the Company’s Surat establishment, William Methwold, who responded at some length regarding the problems in such an enterprise: “Heere is no want of Persian bookes of all sorts, most men of quality in this citty and kingdome being either Persians borne, discended from them, or educated in the knowledge of that language; so that Persian bookes are plentifully to be had (…) [But] the Persian is very difficultly read and understood but by them which are conversant therein”.

However, in the eighteenth century, these difficulties were overcome, as Company employees came to apprentice themselves in a variety of ways into the Persianate knowledge-system. In this talk, I trace some of these cases, notably that of the Scotsman James Fraser, whose extensive collection of texts and images can now be found in the Bodleian Library. Using these materials, I will also explore the forms of cosmopolitan knowledge in a great Indian Ocean port-city, as well as its material supports.

September 19

PANEL I: DISSEMINATION

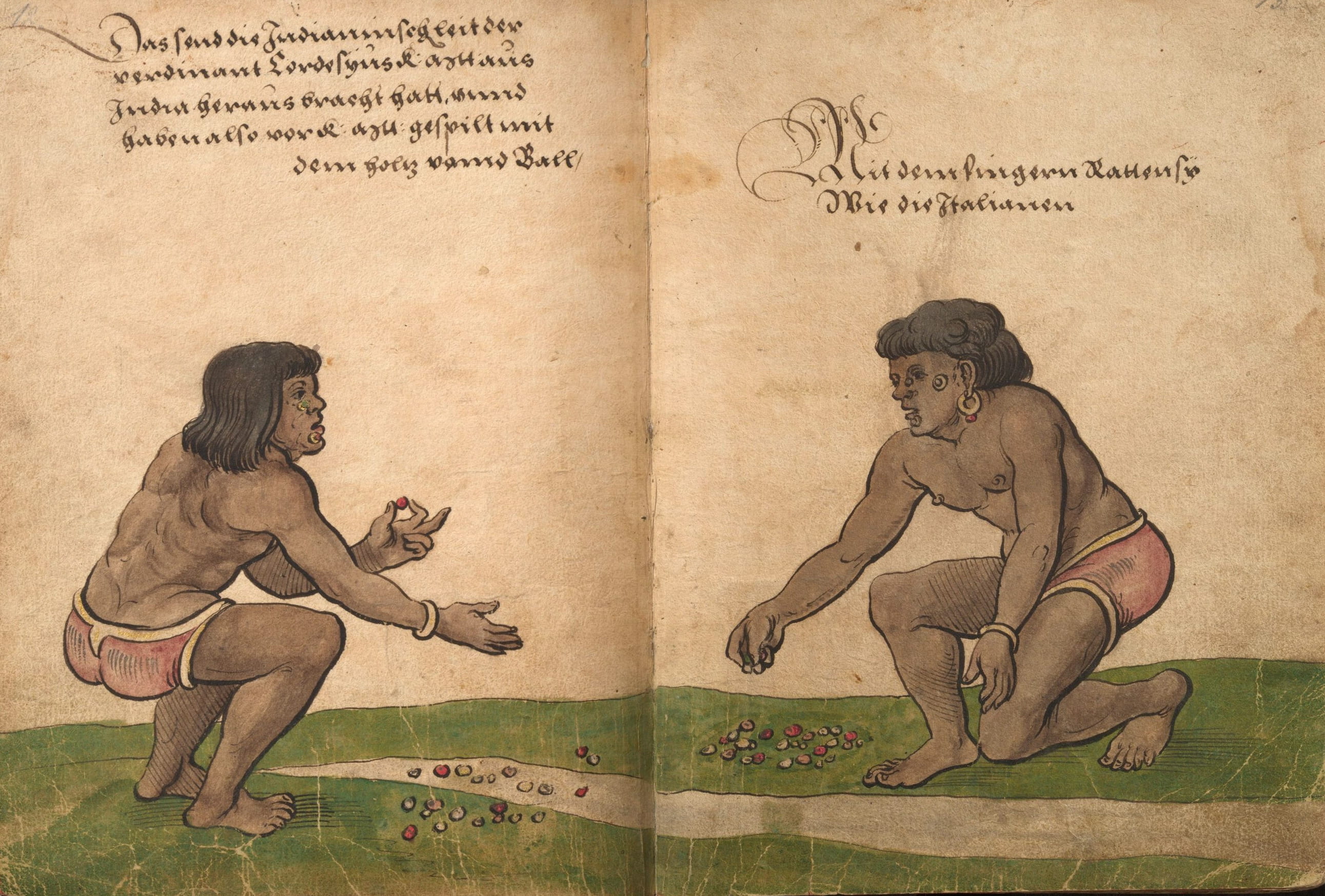

Congealed Circulation, Mediterratlantic Slavery, and the Costume Book of Christoph Weiditz

Byron Hamann, Assistant Professor, Department of History of Art, The Ohio State University

Much has been written on the supposed origins of the nation-state in the sixteenth century, as well as on early modern “European othering”: the creation of interchangeable enemies east (Ottomans) and west (Native Americans). This talk reconsiders these assumptions through an artifact of congealed circulation–an album of paintings–that is the product of three intersecting journeys made in the late 1520s and early 1530s. Now housed in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, Augsburg-based metalsmith Christoph Weiditz’s “costume book” contains 154 brightly-colored pages of men and women and their striking clothes. It is a thoroughly Mediterratlantic compilation, bringing together Muslims from Granada, indigenous people from the Americas (either New Spain or Brazil), and a varied assembly of European Catholics (from Toledo to Genoa to Vienna to Holland)–including a self-portrait of the artist. It is one of the first costume books created in Europe, a genre that would not explode in popularity until three decades later–and in those later print manifestations of the genre, Weiditz’s watercolors take on a new life. After tracing this history of replication forward in time, I return to the source watercolors and what they reveal about space and hierarchy. Instead of “Spanish dress” opposed to “Italian dress” opposed to “French dress” in these images, we find instead the labeled costumes of cities, kingdoms, and regions. And instead of easy oppositions of Europeans versus Others (Muslims, Native Americans), we find striking visual homologies that disrupt facile two- or three-part divisions of the world. In other words, the paintings of Weiditz’s costume book revel in visual difference, but that difference is not easily reduced to hierarchy.At the same time, however, difference and hierarchy were foundational to early modern societies, and no more so than in the practice of slavery. And yet the geography of slavery in the sixteenth century was extremely strange and complex, binding the Atlantic and Mediterranean worlds in commercial networks quite different from those which developed with the rise of industrial capitalism in the late eighteenth century. This geography, too, is preserved for us in Weiditz’s album.

How to Become a Successful Pamphleteer and Author in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire

Nir Shafir, PhD Candidate, Department of History, University of California, Los Angeles

We imagine Islamic manuscripts to be luxury objects: large tomes bound in fine leather, gilded, even illustrated. Yet the material record of early modern Islamic manuscripts tells a different story. Millions of manuscripts were produced in the early modern period and most were short, small, and cheap. How were these cheap books circulated and exchanged? What were the implications of their mass circulation? This paper examines one type of cheap and popular manuscript—the polemical pamphlet—through the works of one of the Ottoman Empire’s most prolific pamphleteers—Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulusi. I argue that Nabulusi pursued particular strategies and utilized specific networks to spread his works from Damascus across the empire while maintaining authorial and textual integrity. In particular, these strategies were a response to the loose notions of authorship and attribution that his ideological enemies employed in the vicious religious debates of the seventeenth century. The paper thus demonstrates the circulatory capacity and flexibility of the manuscript format in a space not controlled by the market as well as the changing position of authors who relied on it to engage new publics.

Colonial Surfaces: Prints, Loss and Latin America

Aaron Hyman, PhD Candidate, Department of History of Art, University of California, Berkeley

Dana Leibsohn, Professor, Department of Art, Smith College

In the early modern period, European prints circulated in remarkable numbers in the Spanish Americas, yet these prints have all but disappeared. In Mexico and Peru, Bolivia and Guatemala, historians have been left to look at prints sideways, through the indices of their circulation: in a massive painted composition that cleaves to a European print source, for example; or in the printed images of saints mentioned in indigenous wills. The presence of prints can be sensed, but rarely are they seen. While historical and art historical accounts of European prints in colonial Latin America often lament this loss, they also tend to minimize its importance by using extant examples of prints in European collections to illustrate the types of objects that once were known in the Americas, but that are no longer.

In this talk, we wish to suggest how loss itself might be an important and useful category to think with. We ask what kinds of histories are rendered insignificant when our interpretations glide (usually quickly) from loss in colonial Latin America to recovery in contemporary European collections. Such interpretive work is premised upon the print existing in multiples, and in being the “same” across given material instantiations. But what do we lose when a single impression disappears?

Taking up the charge of this conference to move beyond viewing prints as primarily vehicles for iconographic transport from one locale to another, and to instead consider their materiality and objecthood, this talk focuses on the surfaces of printed objects and the materials that accreted upon them to suggest why histories of touching, spilling, folding, and marking paper objects are histories worth knowing. Because it is also the loss of such histories that concerns us, we consider the ways in which loss—rather than recovery, circulation, or even materiality—can be a productive lens for understanding colonial practices of the early modern world.

PANEL II: TRANSLATION

Going viral? Maerten de Vos’s St Michael the Archangel

Stephanie Porras, Assistant Professor, Department of Art History, Tulane University

Did early modern prints “go viral”? This paper explores the potential of contemporary network theory on viral videos and Internet memes for assisting historians of early modern print culture. The appeal of viral media theory is its acknowledgement of existing structural constraints and the role of key content gatekeepers. Viral theory allows for chance and contingency, and reverse-engineering the viral event, the goal of many modern marketers and corporations, is often impossible. Crucially too, the term “virality” in contemporary media theory reconfigures the biological notion of contagion (a disease passed on from one unknowing individual to another), as one of sociological action: viral content requires agency on behalf of individuals who choose to “pass on” or forward viral content.

This paper probes three key aspects of viral phenomena apparently shared with early modern print culture – speed and reach, copying and forwarding, as well as the role of networks, gatekeepers and the question of agency – in each case testing the limits of the conceptual model and suggesting how this approach generates further questions for research. By tracing the various pathways of de Vos’s 1584 St Michael the Archangel, engraved by Hieronymus Wierix and first published in Antwerp, this paper charts the movement of a single print through time and space: simultaneously copied by assiduous print publishers, used as a model for devotional imagery in Spain, the American viceroyalties, and the Habsburg possessions in South Asia, as the print was forwarded along often overlapping commercial, social, political and religious networks. Using viral media theory as a guide, I examine the role of individuals and institutions – artists and patrons in Lima, merchants in Venice and Seville, international print publishers and dealers, pedagogical and devotional institutions like the Jesuit order – in redeploying the print in new contexts. The apparently global appeal of De Vos’s St Michael the Archangel thus illustrates both the appeal and the limitations of early modern prints’ “virality.”

Copying Contexts: Picturing Places and Histories in Udaipur Court Painting and Picart’s Atlas Historique

Dipti Khera, Assistant Professor, Department of Art History and Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Several artists forged material-visual translations and global connections at the turn of the eighteenth century in creating pictorial responses to drawings and paintings circulating among kings, connoisseurs and workshops at regional South Asian courts, and among collectors, publishers and travelers in Europe. Based on a court painting depicting the regional king of Kota in northwestern India, an unnamed artist based at the regional court workshop at Udaipur made a painting in c. 1700, inscribed as the “Feeling of the Kota palaces.” The Udaipur painter’s choices show that in adapting the Kota artist’s version, he laid greater emphasis on picturing the bhāva or the feeling or emotion of the represented palace than depicting the likeness of the king or producing a copy that privileged the original painting as a fixed image. Based on the original version by the Kota artist, in the following years, Bernard Picart made an engraving which was published at Amsterdam in the multi-volume book Atlas Historique (1719). This book locates the engraving as a historical image of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and his grand palace; it employs the image to narrate a story of the genealogy and splendor of the Mughals to the world. Unlike the pictorial transformations in opaque gouache seen in the Udaipur painter’s Feeling of Kota Palaces, Picart’s engraving exhibits an emphasis on dense lines and stippling in ink and a treatment of the original version as an absolute image. The corporeal relations both objects produce for their audiences – as a print in a book and as a large-scale painting that was held for its courtly connoisseurs – are equally distinct.

Departing from scholarship that brings these diverse images and practices into conversation primarily for the purpose of dating and identifying the miniaturized portrait of the royal figure, and drawing distinctions in regional painting styles, this paper draws attention to how the works open a window into the artists’ processes of looking and making. Both the Udaipur artist and Picart offer us a rich archive to discern artistic approaches and intellectual thinking on visualizing places and histories across the globe in comparative and connected ways. Between the copying and transformation of contexts in lays a concern to imagine chorography and chronology in newly emergent genres.

Emblematic Technologies: Knowledge, Scientific and Moral, between Copperplate, Woodblock, and Ink Painting

Hansun Hsiung, PhD Candidate, Depts. of History and East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University

Reminiscing, in 1799, on his first encounter with a Dutch copperplate print, the Japanese artist and scholar Shiba Kōkan (1747-1818) waxed effusive. Their “exceeding precision,” he wrote, “approached that of reality itself,” and “while what was written was difficult to translate, one could often, by contemplating the images, penetrate the meaning of the text.” Indeed, over a career that spanned five decades, Kōkan established himself as one of early modern Japan’s foremost practitioners of copperplate etching and engraving, advocating for their incorporation into the common repertoire of native visual production. The dissemination of European scientific knowledge occupied the bulk of Kōkan’s early years. Despite his piecemeal literacy in Dutch, Kōkan emerged as a major proponent of the heliocentric system, copying prints from Dutch works to produce vernacular astronomies for Japanese audiences. Kōkan’s later years then witnessed a movement toward the moral side of popular enlightenment. In addition to exhortatory essays issued from semi-retirement, urging readers to educate themselves in world affairs, Kōkan also began work on an illustrated collection of maxims from the Chinese classics, taking as his model the Dutch emblem books that had come into his possession.

The history of science has, in years of late, turned toward the study of illustrations both as means of scientific communication and as a marker of epistemological assumptions. Meanwhile, book history and bibliography have enhanced our understanding of the circulation of prints, from collectors’ albums to Grangerized codices. Building upon these two bodies of scholarship, as well as a rich tradition of studies of emblemata, my presentation seeks to ask how it is that knowledge in the form of the image comes to be transmitted and translated under different material circumstances of production. Specifically, I examine the vectors of moral and scientific understanding enabled and precluded in the transition from copperplate to woodblock, as well as to manuscript and ink painting.

I begin with an investigation of how Kōkan compiled and copied prints from Dutch texts for his two most significant astronomical works, the Oranda tensetsu [Dutch Discourse on the Heavens] (1796), and Kopperu tenmon zukai [Copernicus’ Astronomy Illustrated] (1808), examining not only printed versions of these works, but also manuscript copies that passed through private hands, demonstrating the manner in which these varied technologies of page-bound inscription revealed alternative approaches to scientific culture. I then turn to the fair copy of the two volumes of Kōkan’s Kinmō gakai-shū [Collection of Maxims Explained by Images], begun in 1814, but left unpublished before Kōkan’s death. Kōkan had earlier on mined prints from multiple Dutch emblem books, such as Jan Luycken’s Het menselyk bedryf (1694), to create various quasi-ethnographic expositions of Dutch customs and manners. The Kinmō gakai-shū, in contrast, represented a more sustained meditation by Kōkan upon the meaning of the zinnebeeld, or emblem, fragments of which scatter his late writings. How were the formal structure and allegorical function of emblems dependent on the composite technologies of image- and text-making? And what happened when these technologies were removed?

PANEL III: RETICULATION

The Early Arrival of Print in Safavid Iran: Port Cities, Global History, and the Armenian Printing Press of New Julfa (1636-1650, 1686-1693)

Sebouh David Aslanian, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of California, Los Angeles

In 1636, Safavid Iran’s first operating printing press was set up in the Armenian mercantile township of New Julfa, a suburb of the Safavid imperial capital of Isfahan. One of nineteen printing establishments owned and operated by Armenian printers during the early modern period (1500-1800), the Julfa press preceded the setting-up of a Persian press by almost two hundred years. On the basis of a collection of mercantile and other correspondence stored at the Archivio di Stato of Firenze, as well as colophons of Armenian books printed in New Julfa, Sebouh Aslanian’s talk explores the little-known history of Armenian print culture in Isfahan during the course of the seventeenth century. The talk will examine the history of Julfan print against the larger backdrop of print culture history both in Euroamerican as well as within the Islamicate world. It will emphasize how, even in land-locked Julfa, the future viability of an Armenian press in seventeenth-century Iran was shaped by Julfa’s access to port cities and especially to the mercantile patronage of their port-Armenian communities that also sustained other Armenian printing presses during the early modern period. The talk will conclude by exploring the early divergence between Armenian and Islamic print trajectories. It will probe some of the reasons for why unlike Perso-Arabic print, which became part of the globalization of print culture during the nineteenth century, the Armenian print trajectory was already underway at the dawn of the early modern period.

The Harvard Indian College and the Emergence of a Collaborative, Multilingual American Literature (1650-75)

Lisa Brooks, Associate Professor, Depts. of English and American Studies, Amherst College

The first bible published in America has long been called the “Eliot” bible, named for the missionary John Eliot, its purported author. Yet recent scholarship shows that Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God was translated and printed in a multilingual, bicultural space of collaboration, which included Wampanoag and Nipmuc scholars who attended and were housed at the Harvard Indian College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This paper will explore the origins of early American literature through the lens of the Harvard Press and its bilingual publications, focusing especially on the education and contribution of Caleb Cheeshateamuck, Harvard’s first Native graduate, and his classmates Joel Iacoomes and James Printer. It will consider the circulation of the texts of the “Indian Library” and the significance of the press (including the type) that produced it. The circulation of these texts, as objects and instruments, in Native communities will be discussed within a longer tradition of literary media and “intellectual trade routes” in Indigenous networks of exchange. Most important, copies of these collaboratively-authored bilingual texts continue to circulate, playing a vital role in the revitalization of Indigenous languages today.

PANEL IV: CULTIVATION

The Devanāgarī Press of Serfoji II of Tanjore: The Printed Book and Vernacular Modernity at a Colonial Indian Court

Indira V. Peterson, Professor, Department of Asian Studies, Mount Holyoke College

The hand press established in 1807 at the small south Indian court of Tanjore by the Maratha ruler Serfoji II (r. 1798-1832) marks an important episode in the history of print in South Asia. Educated by German missionaries, Serfoji was a pioneer of modernization in colonial India. Equipped with imported fonts and run by brahman pandit scholars, between 1808 and 1814 the palace press, the first devanāgarī press in colonial south India, produced eight books in Sanskrit and two in Marathi, for use as textbooks in the schools established by the court for disseminating “New Learning” (navavidyā). The imprints included first editions of Sanskrit classics, along with several firsts in Marathi printing — the first south Indian Marathi books printed in devanāgari script, and the first complete translation of Aesop’s Fables into an Indian language, also the earliest example of modern Marathi prose. Despite the preponderance of Sanskrit books in its output, Serfoji called his press a “Mahratta” press, clearly intending it to be a vehicle for turning Marathi, a minority language in polyglot south India, into a viable vernacular language for modern knowledge.

In this paper I examine the material and intellectual aspects of two Tanjore press books –the Sanskrit lexicon Amarakośa and the Marathi Aesop– and their production by brahman pandits. My goal is to illuminate the choices and contestations entailed in Serfoji’s deployment of print as an instrument for imagining a vernacular modernity that, like comparable –and mostly later—initiatives in South Asia, would effect major shifts in linguistic hierarchies and practices of literacy and learning. Serfoji’s print project anticipated or intersected with those of other constituencies (missionaries, the colonial government, urban middle classes) in many respects. However, the particular nexus he created through print, among Sanskrit, Marathi, and European learning, was designed especially to ensure the influential participation in vernacular modern education by Maratha courtly elites and brahman scholars. Among the strategies that Serfoji used to achieve his goals were: fixing, through the use of the shared devanāgarī font (devanāgarī was not the default script used for either language), extant connections between Sanskrit and Marathi; and the transformation of brahman literati into artisans of the press and makers of books for both the traditional and the Anglo-vernacular curriculum. My study of the early 19th-century Tanjore press argues for historiographies attentive to the plural, complex, and idiosyncratic nature of the relationship between print and vernacular modernity.

Islamic Bengali Literature’s Trajectory from Manuscript to Print: The Politics of Language, the Archive, and Literary Historiography

Ayesha A. Irani, Assistant Professor, Department of Religion, University of Massachusetts-Boston

This paper examines two different strands of Islamic Bengali literature, produced for different kinds of audiences and reading publics, over four centuries. In order to spread the message of their faith among East Bengalis, Muslim intellectuals first began to write in Bengali some time in the sixteenth century. They enriched Bengali’s literary heritage with a range of new genres and texts that drew upon Perso-Arabic counterparts both in form and substance. From what we know of their manuscript circulation, many of these texts were extremely popular, in certain regions of East Bengal, and were written in Bengali, Arabic, and Kaithi (or Sylhettee Nagari) scripts. Yet when the printing press came to Bengal in 1800, most of these texts failed to make the transition from manuscript into print. Instead, urban Muslims of Calcutta, Hooghly, and Dacca, began to now compose literature for the publishing industry in a new artificial strand of Bengali that came to be designated by colonial linguists as Musalmani Bangla, which was printed mostly in Bengali but also in Kaithi (or Sylhettee Nagari) scripts. I examine the reasons for the failure of the old and the success of the new literature in the competitive and communalized environment of language and print culture in Bengal.

The emergence of Bengali prose as a respectable literary form converged with print culture in the nineteenth century to create a vibrant market for periodicals, a large proportion of which were devoted to the prodigious production in contemporary literature, and lively debate on matters of religion and social reform. Stimulated by orientalist enterprises such as the Asiatic Society (of Bengal) founded by William Jones in 1784, the Bengali intelligentsia created the Bengal Academy of Literature in 1893—renamed a year later as the Vaṅgīya Sāhitya Pariṣad. The institution’s mandate was to collect, preserve, and study the artifacts of Bengal’s history and literature. The Pariṣad’s periodical regularly published its inventories of Bengali manuscripts that its members in all its numerous branches were assiduously collecting. These catalogues showed that Islamic Bengali manuscripts were not excluded from this collection effort, and constituted a part of this early archive. The first articles and books on Bengali literary historiography began to emerge as early as 1830. But it took more than an entire century before Islamic Bengali literature was even nominally placed on Bengal’s literary map. This paper will trace why and how this happened, delineating the initial erasures and eventual recognition of the contributions of Muslim authors to Bengali literature by East Pakistani and Bangladeshi literary historiographers.

The Journal of Sichuan Studies, Western Learning, and Classical Studies in Late Nineteenth-Century China

Cynthia Brokaw, Professor, Department of History, Brown University

The Journal of Sichuan Learning (Shuxue bao 蜀學報), printed in only thirteen issues in 1898, was a publication of the “Revere the Classics” Academy (Zunjing Shuyuan 尊經書院), the most prominent center of classical learning in Sichuan province during the Qing period (1644-1911). The stated goal of the journal was twofold: the mastery of the Chinese Classics for practical governance—that is, the application of the principles of China’s ancient sages to the specific political and economic problems of the day; and the introduction of Western learning, in particular mathematics, to academy students. It had another, unstated, goal as well: the dissemination to the farther reaches of China Proper of the reform ideas developed in Beijing, the political center, to strengthen the dynasty against further inroads by Western and Japanese imperialist nations.

The contents of the journal reveal the struggles of provincial intellectuals to come to terms with the need for reform and with the nature and implications of the new ideas and institutions from the West that had influenced the central call for reform. Some articles assert the superiority of Chinese values, arguing that filial piety and ritual propriety are the only means to good governance (which, it was assumed, would automatically pave the way for the expulsion of the foreigners who were impinging on Qing sovereignty). Others bespeak a faith in concrete “statecraft” measures—improved transportation networks, the development of mining, etc.—shaped by knowledge of Western technologies. And others report news from the West as filtered through the modern Chinese newspapers of the eastern seaboard.

I focus on articles that reveal the efforts of academy students and teachers to apply their classical training to the new Western learning, specifically on ones that purport to introduce the principles of international law as set forth in Wanguo gongfa 萬國公法 (1865), the Chinese translation of Henry Wheaton’s Elements of International Law, in terms of the principles guiding inter-state relations in early China as revealed in the ancient classic, The Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu春秋).

But I am also interested in considering the ways in which the format of the journal shaped the presentation of its intellectual and political agenda. Published as a traditional woodblock text, Sichuan Learning nonetheless adopted many of the features of modern Western-style periodicals produced in Shanghai. How did the mixture of formatting and editorial styles influence the reading experience and most particularly the vision of reform pre